UN Secretary General Dag Hammarskjold began his career as a Swedish civil servant and economist. Although the United Nations is headquartered in New York and Hammarskjold made a huge impact on the organization, setting the standard by which every other Secretary General would measure themselves, he is not widely known to Americans. We sat down with Sara Causey, host and resident blogger at the con-sara-cy theories podcast, to better understand Hammarskjold and his legacy of quiet diplomacy.

You often discuss Dag Hammarskjold on your podcast and blog. What inspired your interest as an American in his life?

I came to the topic of his life and legacy in a backwards sort of way, I’d say. My interest in Dag Hammarskjold actually started with the bizarre details of his death, which was supposedly by tragic accident. However, upon any real examination of the evidence, it seems pretty clear that there was much more at play. From there, I started to wonder, “Who was this person? What did he believe in? What did he stand for? What enemies did he have?” What I discovered was someone so completely different from anyone else I’d ever studied. Dag was a remarkable person and, I would also say, a truly gentle and wonderful soul. If that sounds a little mushy, I’ll plead guilty.

The United Nations is prominently headquartered in New York City. Why do you think Americans in general lack an awareness of Hammarskjold?

Overall, I would blame it on the American public’s lack of interest in history. There have been a number of studies relaying that the majority of American adults cannot read at a sixth-grade proficiency level. That’s depressing, but not surprising. Social media has spoiled us to instant gratification and quick sound bites. People gravitate to flashy headlines and tawdry Hollywood gossip in a lot of cases. I would also say that, just as many Americans cannot really pinpoint and explain the function of the Fed, they likewise cannot pinpoint and explain the function of the UN. Hammarskjold took his role as the Secretary General seriously and sought to use “quiet diplomacy” as a means to prevent warfare and bloodshed.

How would you describe that “quiet diplomacy?”

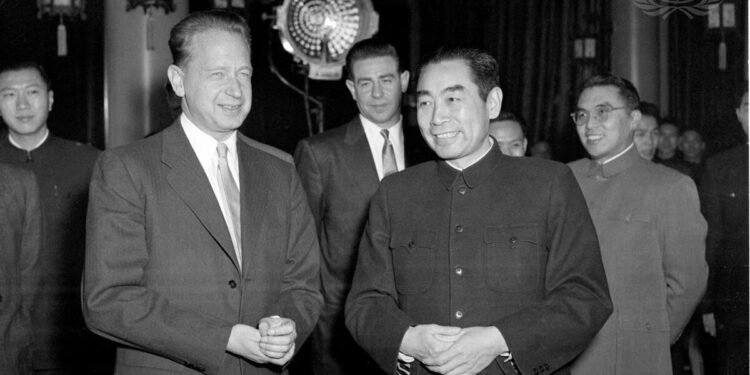

I think Hammarskjold’s own words are useful. In a 1955 interview with Alistair Cooke, Dag said that it is impossible to negotiate without a “reasonable degree of secrecy.” Yes, include the news media and include transparency where possible, but still while asking for a sense of quiet in order to achieve the best possible result. So for Hammarskjold, it was not about secrecy for its own sake or secrecy in the sense of shady back room deals, but rather the space to hear each side in a conflict and seek common ground without outside forces derailing the proceedings while still in a delicate state. In the same interview, he talks about his role as a trustee for 60 nations and how important it was to exercise discretion in such a position. At that time, a group of American airmen had been detained in China. Their families in the US wanted them safely returned home, of course, which the Chinese government had threatened not to do. Hammarskjold was sent to open a door with Zhou Enlai, the Premier, for the release of these airmen. Hammarskjold told Cooke that he considered himself to be a trustee of the airmen themselves and, as their agent in the free world, he did not ever want to say anything or seek out publicity that would harm their interests. If only diplomats and politicians had the same attitude today! Anyhow, Hammarskjold was indeed able to open that door and, for his fiftieth birthday in late July, Enlai said he would release the airmen as a personal gift to Dag. On August 1st, President Eisenhower offered a statement thanking the UN and Hammarskjold in particular for the humanitarian efforts involved. Rather than bragging on himself, Hammarskjold privately wrote that God did the work while he held the can of paint below.

Do you feel that type of attitude is lacking in contemporary politics and, if so, how could it change things in the US?

Yes, I would say it is assuredly lacking. It seems to me that there is a real emphasis on who can shout the loudest and try to hog any sense of credit. I think Dag had a strong commitment to the overall idea of public service – and not in some phony sense to garner praise or votes. I think he had a true, deeply held conviction toward helping other people and building a life of service. Was he perfect? No, of course not. No human being ever is, but he was a man of conviction. Edward R. Murrow used to have a CBS radio program called “This I Believe.” What a perfect show for Hammarskjold! If you listen to his segment – which you can still find online in Dag’s own voice, which is a nice added bonus – he talks about inheriting from his father’s family the sense that selfless service produces a life worth living and from his mother’s family, he inherited the sense that all people were equal under God. Everything now is about noise – who can shout the loudest, who can be the most brash, who can run the sleaziest attack ads on TV. Then you encounter someone like Dag Hammarskjold, who championed the UN’s meditation room of quiet, and it reminds you how impactful that kind of stillness and gentleness can be. If we stopped paying attention the loudest voices and the nastiest rhetoric, we just might get somewhere. Studying Dag’s contributions to diplomacy certainly offers us a starting point.

New episodes of the con-sara-cy theories podcast drop every Wednesday night at 7pm Central / 8pm Eastern time. You can find it on any major podcast provider.